#2. Of Putrajaya, Amnesic Utopias, and The City of Omelas

"I’m thinking of something a friend once told me, that violence has many masks. Some of those masks look like a pristine city."

This week, I’m publishing an essay I’ve been working on for a while (of which a much shorter, initial draft was actually rejected by a government-funded writing program I was a part of for not adhering to their, ahem, “pillars”.)

This essay looks at our country’s infamous administrative capital, the invisible contracts of happiness, and a story by one of my favorite sci-fi writers.

Many thanks to friends who read drafts of this essay and provided valuable feedback.

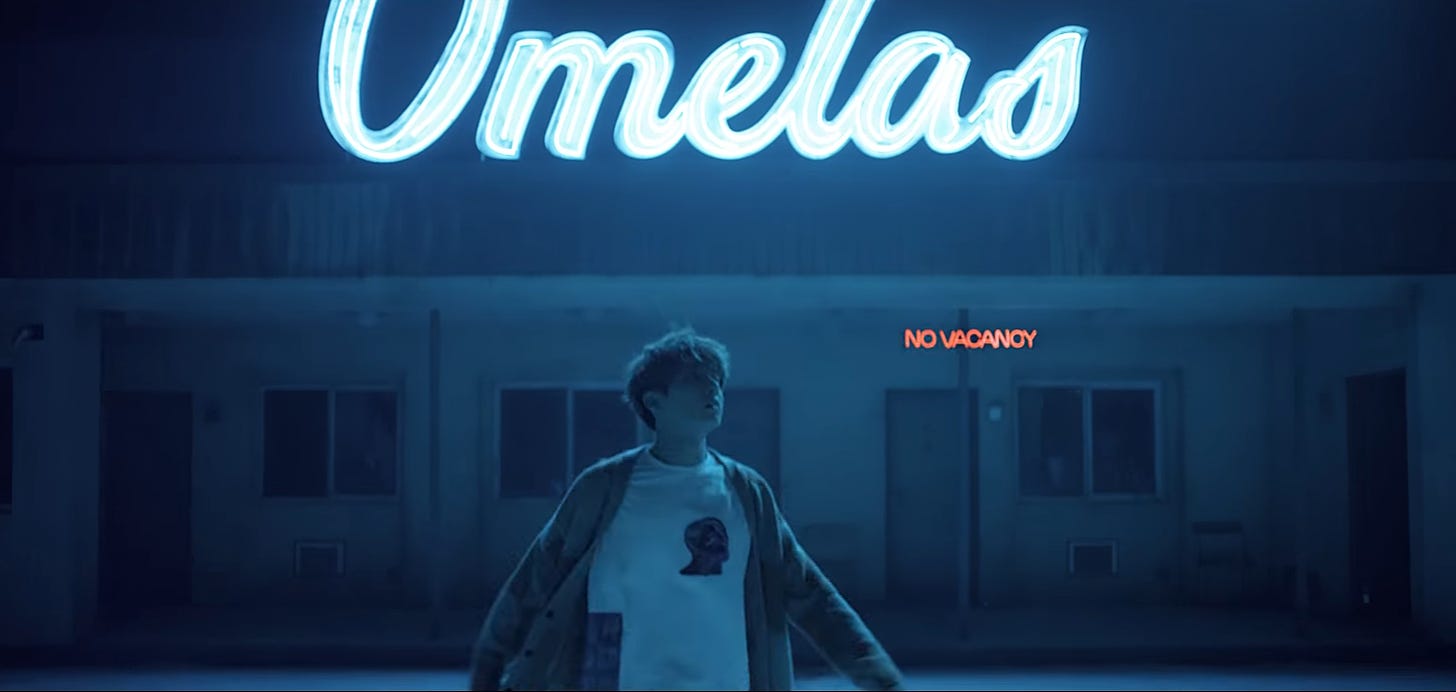

In her 1973 short story, The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, science fiction writer Ursula K. LeGuin tells the story of Omelas, a seemingly utopian city that has it all. The story opens with a celebration in Omelas, the city air rich with a sort of giddiness, festivity, and happiness. It is a fact that LeGuin highlights frequently in this short story, that people of Omelas are a happy people — but, she makes a point to highlight, “they were not naïve and happy…they were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched.”

The story of Omelas takes a dark swerve about halfway through, when we learn that underneath Omelas lives a small child. A small child who has been caged, neglected, and irreversibly damaged. It becomes clear, too, that the success of Omelas depends on, for whatever reason, the suffering of this child.

“They all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children […] depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery,” writes LeGuin.

I’m thinking of Omelas more and more these days, as I drive aimlessly through Putrajaya, winding over extravagant bridges and cleanly manicured neighborhoods, driving past rows of ministry buildings and intricately designed mosques, imagining the other lives in this strange city.

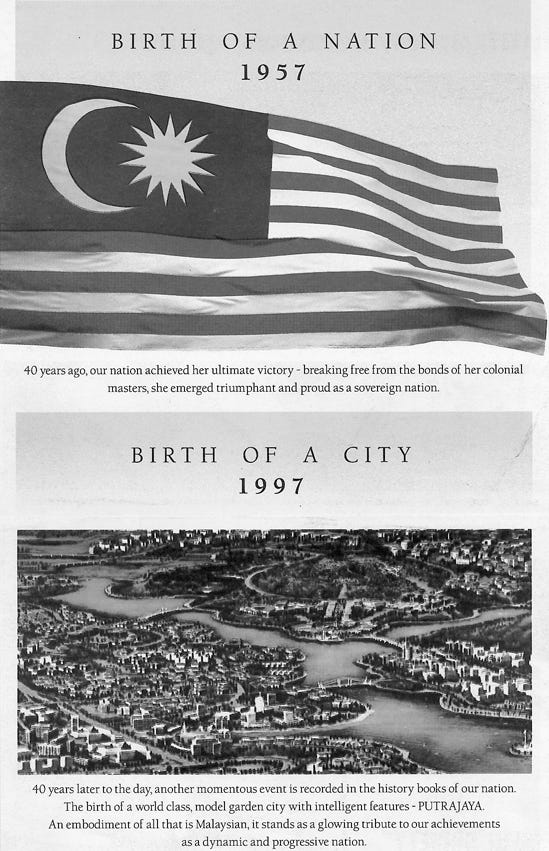

“It’s a city of the future,” said the president of the Putrajaya Corporation about Putrajaya in 1997, four years after it was first conceived. An elaborate part of Mahathir’s Wawasan 2020, Putrajaya’s architecture symbolized Mahathir’s vision for the country’s future: modernity, progress, and technological advancement, with a cultural vision that centered Malay-Muslim nationalism and leadership in the Islamic world.

Putrajaya was supposed to be a Malaysian utopia.

But walking through Putrajaya now feels like walking through an elaborate but obsolete film set of grandiose buildings and bridges. It’s not just that it doesn’t feel like a city of the future—it feels like a city wildly detached from the present.

It’s surreal, in the depths of the coronavirus pandemic, to see this city—empty, opulent, resourced, and quiet—while the rest of the country feels like it’s on fire, trying to survive rising case numbers, frontliner burnout, and an economic failure that has put some families on the brink of starvation.

So I’m thinking of Omelas, of our national utopias, and the dark truths buried underneath.

In The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, LeGuin makes a point to note that those living inside Omelas are not stupid people, despite being happy. Everyone, she notes, was made aware of the sacrificial child at some point in their life.

For LeGuin, this happiness—this acceptance of the status quo, this satisfaction with it—is a calculated decision. She writes, “happiness is based on a just discrimination of what is necessary, what is neither necessary nor destructive, and what is destructive.”

To recognize suffering would be to upend the delicate balance of Omelas—it would be destructive. Accepting suffering as collateral damage, then, becomes necessary to those who decide to stay. Denial becomes part and parcel of citizenship.

“Those are the terms. To exchange all the goodness and grace of every life in Omelas for that single, small improvement: to throw away the happiness of thousands for the chance of the happiness of one: that would be to let guilt within the walls indeed,” LeGuin writes.

What are the terms that a city like Putrajaya must accept, in order to remain pristine?

Primarily, it must remain an amnesic city, constantly forgetting the country around it, and the history that existed before it. It’s a city of erasures.

Populated largely by Malay communities, Putrajaya’s demography articulates who in Malaysia is closest to political power. In 2019, Bumiputras made up 96.7% of the population of Putrajaya, Chinese communities made up 2.1%, Indian communities 1.7%, and other Malaysians 0.2%.

Scholar Tim Bunnell says that this is “probably a by-product of the ethnic composition of the civil service rather than part of any explicit strategy to keep Malays out.” Still, as he rightly notes, it reproduces a national imaginary of a Malay core and a non-Malay periphery.

There are no planned churches, cathedrals, temples, or monasteries, or other sites of worship in Putrajaya. Instead, the Prime Minister’s Office overlooks Putra Mosque and the Palace of Justice, a symbol of the tangled web of power, law, and religion in the country.

Yet, despite the population of Malay communities in Putrajaya, the architecture reflects very little Malay cultural design, utilizing none of the Malay Great Mosque architecture or Malay domestic architecture. As scholar Ross King notes, “there is nothing identifiably Malay in the styling of Putrajaya.”

Instead, Putrajaya uses repeated references to the Middle East and Islamic architecture, as if insisting on a history that is singularly connected to Islam and the Middle East.

“The overwhelmingly Islamic-style buildings are out of place in a country which is dominated by Muslim Malays, but also home to large ethnic Chinese and Indian minorities,” said architect Mohamad Tajuddin to AFP in 2008.

Less noticeable, but certainty more jarring, is the erasure of the communities who existed before Putrajaya. Putrajaya’s development rested on the displacement of four plantations, pushing out 400 mostly Tamil Indian Malaysian families outside of the area. It also included the demolition of temples and shrines.

Tim Bunnell notes that by 2004, displaced workers and their families were living in flats in Dengkil’s Taman Permata, with no provisions made for them in the land they used for farming and income. The flats subjected them to safety and health issues, at times forcing residents to live in tents in the carpark after the flats had been declared unsafe to live in due to unstable foundations and wall decay.

Meanwhile, “the spaceship-like Convention Centre in the south of the city,” he writes, “was by 2004 visible from the Taman Permata resettlement flats.”

These workers had returned to Putrajaya to work as security guards, cleaners, or landscape gardeners, some paid a measly RM700 per month. One man who had worked as a supervisor in Perang Besar had tried to purchase an apartment near in the Putrajaya Hospital in 2000, and was reportedly told that the units were only for Malays.

One worker told the researchers, “nothing is possible (onnume illai) for Indians in Malaysia; everything is possible only for Malays.”

Nearby, other instances of historical forgetting and minority erasure are rampant. To make way for KLIA, for example, Kampung Busut, a Temuan village, was also displaced and resettled in Kuala Langat North Forest Reserve. These same families face displacement again, as KLNFR risks being degazetted and “developed”. The Palace of Golden Horses and The Mines have been built on Sungai Besi, the site of the first phase of the 1937 MCP-linked miners’ strike and uprising.

There is nothing to remember these communities and histories that lived here before Putrajaya. Why does our national development demand that our histories be forgotten?

As I’m driving down the city today, I’m thinking of something a friend once told me, that violence has many masks. Some of those masks look like a pristine city.

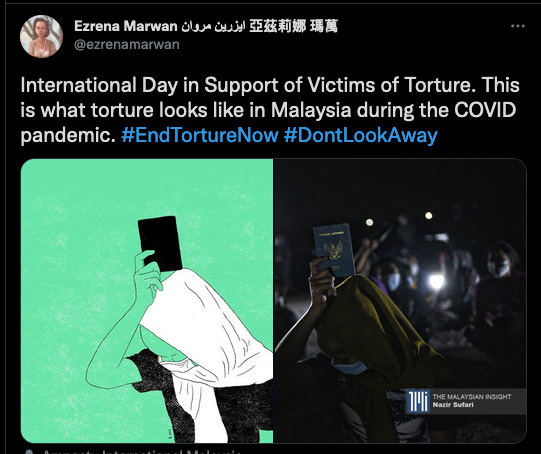

This past year, more than any other year that I’ve lived in Malaysia, death, violence, and harm hang in the air like a thick fog. A few weeks ago, we passed the million-mark of people who have been infected with COVID-19 since it was first detected in January last year. Over 13,000 people have died from the virus. In the worst economic decline since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, Malaysians hung white flags outside of their homes, calling for help to feed themselves and their families. Politicians asked to take them down. Contract doctors walked out in a nationwide strike and were threatened. Activists calling for better working conditions for hospital cleaners were arrested charged. A string of Indian Malaysians have died in police custody to date. Migrants and refugees have been detained, chained, sprayed with disinfectant, sent to detention centres that have been described as torture-like, and deported.

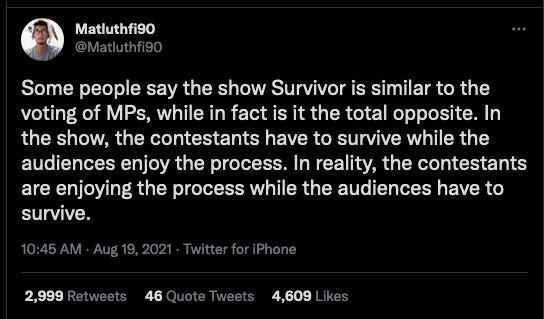

Meanwhile, politicians have been flouting MCO rules with little repercussion. Some have left for France and Turkey, ostentatiously posting on their social media. Others have called the white flag movement a conspiracy. As I’m writing this, our Prime Minister has stepped down, leaving power struggle between the same politicians who used the pandemic as a space to accrue gains.

I’m thinking again about LeGuin, who says that those who are happy are not stupid. They have decided whose suffering is necessary. They have decided which realities to deny.

At the end of LeGuin’s short story, there are people in the city who decide the suffering is unacceptable. They walk away from Omelas and into an uncharted and uncertain future.

“They walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going,” she writes.

I think of the ways we Malaysians have reached into the dark, trying to put together a new future. I think of #kitajagakita and creative MCO-compliant protests and acts of solidarity. I think of the ways Malaysians are yearning for a future and a government that will protect and care for them. I think of the ways we have tried to care for ourselves now.

I think of LeGuin, and her definition of happiness. How much of it is about accepting the status quo, even when you’ve seen it. I think about the people who left Omelas. It’s not about leaving, per se, but about rejecting. It’s about refusing to accept the status quo. It’s about resisting the violence of the present, and moving into a new future—one buoyed by the promise where human suffering is not a byproduct of the design.

We certainly should not be building more cities under an ethnonationalist vision, but perhaps there is one hopeful lesson embedded in Putrajaya’s architecture. Perhaps that lesson is that it is indeed possible to envision and build something new and different out of the past. That something new and more radical can be imagined into the future, no matter how seemingly out of reach.

Lovely piece, Lily. Nice to see you writing here, look forward to more <3